Floating point numbers#

In the following, we explore how computers represent numbers. Integers are the simplest to understand. A computer can only represent a finite range of integers, for example, some implementations can store integers between \(-2^{63} = -9223372036854775808\) and \(2^{63}-1 = 9223372036854775807\).

Next, consider rational numbers such as \(1/3 = 0.33333\ldots\). One might attempt to work directly with fractional expressions like \(1/3\) and keep track of numerators and denominators. However, the number of digits in both the numerator and denominator tends to grow significantly as computations progress, making this approach impractical in most cases. Irrational numbers such as \(\pi\) or \(e\) pose an even greater challenge because they cannot be represented as fractions of integers.

The solution for \(\mathbb{Q}\) and \(\mathbb{R}\) is the same: we must truncate their representation after a finite number of digits, thereby introducing a small error. Complex numbers, in terms of their storage in computer memory, are treated like two real numbers.

Definition of floating-point numbers#

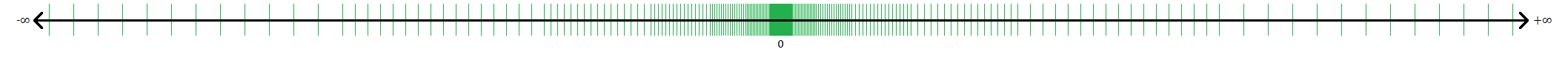

The basic idea behind floating-point numbers is to define a finite subset of \(\mathbb{Q}\) that has a finer spacing for small numbers, allowing computations to account for small quantities, while employing a wider spacing for large numbers, thus covering a large range between the smallest and largest represented numbers.

Definition 2

We call \(\mathcal{F}\) a set of floating-point numbers if lfljgf

for some \(b, p \in \{2, 3, 4, \ldots\}\) and \(e_\min, e_\max \in \mathbb{Z}\) with \(e_\min < e_\max\).

The above rigorous definition of floating-point numbers allows us to prove theorems that consider that computers only support finite-precision arithmetic.

The definition already indicates how the numbers of \(\mathcal{F}\) are best represented in the base-\(b\) numerical system. Most commonly, we look at binary numbers, i.e., base \(b = 2\), and sometimes at decimal numbers, i.e., base \(b = 10\). The factor \((-1)^s\) determines the sign of the number. The factor \(b^e\) determines the position of the leading digit. The final factor \(\frac{m}{b^{p-1}}\) takes values between \(1 = b^{p-1} / b^{p-1}\) and \((b^{p}-1) / b^{p-1} = b - 1 / b^{p-1}\). For large \(p\), we find \(b \approx (b^{p}-1) / b^{p-1}\). Thus, varying the mantissa \(m\) allows us to approximate different numbers, whose leading digit is in the same position:

Example 7

Let \(b = 2\), \(p = 2\), \(e_\min = -1\) and \(e_\max = 1\). It follows that \(b^{p-1} = 2\) and \(b^p - 1 = 3\). Then \(\mathcal{F}\) consists of \(0\) and the numbers enumerated in the following table:

\(s\) |

\(e\) |

\(m\) |

Value |

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

-1 |

2 |

\(2^{-1} \cdot \frac{2}{2^1} = 0.5\) |

0 |

-1 |

3 |

\(2^{-1} \cdot \frac{3}{2^1} = 0.75\) |

0 |

0 |

2 |

\(2^0 \cdot \frac{2}{2^1} = 1\) |

0 |

0 |

3 |

\(2^0 \cdot \frac{3}{2^1} = 1.5\) |

0 |

1 |

2 |

\(2^1 \cdot \frac{2}{2^1} = 2\) |

0 |

1 |

3 |

\(2^1 \cdot \frac{3}{2^1} = 3\) |

1 |

-1 |

2 |

\(-2^{-1} \cdot \frac{2}{2^1} = -0.5\) |

1 |

-1 |

3 |

\(-2^{-1} \cdot \frac{3}{2^1} = -0.75\) |

1 |

0 |

2 |

\(-2^0 \cdot \frac{2}{2^1} = -1\) |

1 |

0 |

3 |

\(-2^0 \cdot \frac{3}{2^1} = -1.5\) |

1 |

1 |

2 |

\(-2^1 \cdot \frac{2}{2^1} = -2\) |

1 |

1 |

3 |

\(-2^1 \cdot \frac{3}{2^1} = -3\) |

A graphical representation (Source Wikipedia) of a floating-point set is

The term ‘floats’ is often used as a shorthand for ‘floating-point numbers’.

IEEE 754#

The previous example is not practical because that \(\mathcal{F}\) is far too small. Instead, the most widely used floating-point sets are defined in the IEEE 754 standard.

The two most common types of floating-point numbers are IEEE double precision and IEEE single precision. The former provides around 15 digits of accuracy, while the latter offers around 7 digits of accuracy.

IEEE double precision: \(e_{min} = -1022, e_{max} = 1023, p = 53\), \(b = 2\)

IEEE single precision: \(e_{min} = -126, e_{max} = 127, p = 24\), \(b = 2\)

For almost all purposes, this is more than sufficient. Take, for example, the gravitational constant \(G\). It is known to around 4 digits of accuracy, only a fraction of the number of digits available in modern computers.

For most numerical calculations, double precision is preferred because, in some computations, errors might accumulate, leading to a loss of accuracy. Double precision provides much more headroom for this than single precision.

However, not all applications require such precision. For example, many machine learning applications use the half-precision type, which is even less accurate than single precision but can be evaluated extremely efficiently on dedicated hardware, e.g., tensor cores on modern machine learning accelerators.

Floating-point arithmetic#

The distance between neighbouring floats with same leading digit is \(2^e b^{1-p}\). Let \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) be between the smallest and largest floating-point number. Define \(\epsilon_{mach} := \frac{1}{2} b^{1-p}\). There exists \(x' \in \mathcal{F}\) such that \(|x - x'| \leq \epsilon_{mach} |x|\). In words, \(\epsilon_{mach}\) is the relative distance to the next floating-point number in \(\mathcal{F}\).

Define the projection

where \(fl(x)\) is the closest floating-point number in \(\mathcal{F}\). If there are two floating-point numbers of equal distance choose the one with smaller absolute value. It follows that \(fl(x) = x \cdot (1 + \epsilon)\) for some \(|\epsilon| \leq \epsilon_{mach}\).

Theorem 2 (Fundamental Theorem of Floating Point Arithmetic)

Define \(x\odot y = fl(x \cdot y)\), where \(\odot\) is one of \(+,-,\times,\div\). Then for all \(x,y\in\mathcal{F}\) there exists \(\epsilon\) with \(|\epsilon| \leq \epsilon_{mach}\) such that

Most modern computer architectures follow the mathematical assumptions about floating-point sets to guarantee the Fundamental Theorem. For additional details we refer to the recommended lecture book [Trefethen and Bau, 1997].

Python skills#

The NumPy module provides convenient tools to query the properties of floating-point numbers. First, import NumPy as follows:

import numpy as np # Import the numpy extension module and alias it as np

Floating point data types in NumPy#

NumPy defines the following data types for floating-point numbers:

IEEE double precision:

np.float,np.double,np.float64IEEE single precision:

np.single,np.float32

Querying floating-point properties#

Use np.finfo to query floating-point properties. For example:

double_precision_info = np.finfo(np.float64)

Key properties of double precision floating-point numbers:

Maximum value:

double_precision_info.maxSmallest (absolute) normalized value:

double_precision_info.tinySmallest relative difference (machine epsilon):

double_precision_info.epsApproximate relative precision:

double_precision_info.precision

Illustrative examples:

1 + double_precision_info.eps # Just larger than 1

1 + 0.25 * double_precision_info.eps # Slightly closer to 1

Special floating-point values#

The floating-point standard also defines:

NaN: Not a numberinf: Infinity

Examples:

a = np.inf

b = np.float64(0) / np.float64(0) # Produces NaN

print(b) # Output: nan

Note: NumPy adheres to the IEEE 754 standard, so operations like division by zero return

NaNrather than raising an error.

Python itself is not fully IEEE 754 compliant. Consider:

a = np.inf

b = 0. / 0. # Raises ZeroDivisionError in Python

This behaviour is one reason why NumPy is critical for numerical computations in Python, as it adheres more closely to the IEEE 754 standard.

Self-check questions#

Question

Explain the meaning of \(\epsilon_{mach}\).

Answer

\(\epsilon_{mach}\), known as machine epsilon, is defined as:

where \(b\) is the base and \(p\) is the precision. It represents half the distance from 1 to the next floating-point number and quantifies the maximum relative error between a real number \(x\) and its closest floating-point representation \(x'\). Mathematically:

Question

Why do double precision numbers give you around 15 digits of accuracy?

Answer

In double precision, we have:

This means the relative error when mapping a real number to its floating-point representation is accurate to approximately 15 significant digits.

Question

Consider a floating-point system with base \(b=2\), precision \(p=5\), \(e_{\min}=-6\), and \(e_{\max}=6\).

Determine the machine epsilon \(\epsilon_{mach}\) for this system.

Show that any real number \(x\) (within the representable range) can be approximated by a floating-point number \(fl(x)\) such that:

\[ |x - fl(x)| \leq \epsilon_{mach} |x|. \]

Answer

By definition, \(\epsilon_{mach} = \tfrac{1}{2} b^{1 - p}\). Since \(b=2\) and \(p=5\), we have

\[ \epsilon_{mach} = \tfrac{1}{2} \cdot 2^{1-5} = \tfrac{1}{2} \cdot 2^{-4} = 2^{-5} = \frac{1}{32}. \]For any real number \(x\) in the representable range, the floating-point number \(fl(x)\) is chosen as a closest number in the given floating-point set. By definition of the rounding rule,

\[ |x - fl(x)| \leq \tfrac{1}{2}\text{(spacing at scale of }x). \]Since the spacing around a number \(x\) is proportional to \(|x| b^{1-p}\), we have

\[ |x - fl(x)| \leq \epsilon_{mach} |x|. \]This shows that the relative error in representing \(x\) as \(fl(x)\) is bounded by \(\epsilon_{mach}\).

Question

Consider floating-point arithmetic in base \(b\) with precision \(p\). Assume \(x\) and \(y\) are floating-point numbers that do not differ too drastically in magnitude. Show that the computed sum \(fl(x \oplus y)\) satisfies

and discuss the limitations of this error bound when \(x\) and \(y\) differ by orders of magnitude (catastrophic cancellation).

Answer

By the Fundamental Theorem of Floating Point Arithmetic, any floating-point operation on representable numbers \(x\) and \(y\) can be written as

with \(|\epsilon| \leq \epsilon_{mach}\). Thus, for addition,

Hence,

This ensures that addition of two numbers of similar magnitude is highly accurate. However, when one number is much larger than the other, or when \(x \approx -y\) causing nearly complete cancellation, the relative error bound with respect to the smaller or nearly cancelling parts of the sum can be large, leading to loss of significant digits (catastrophic cancellation). While the overall bound still holds in an absolute sense, it may not be meaningful for assessing accuracy in such scenarios.

Question

Consider a floating-point system with base \(b=10\), precision \(p=3\), and exponent range \(e_{\min}=-2\), \(e_{\max}=2\). Given a real number \(x=1.23456\), determine its floating-point representation \(fl(x)\) and estimate the relative error \(\frac{|x-fl(x)|}{|x|}\). Compare your computed relative error with \(\epsilon_{mach}\).

Answer

Floating Point Representation: With \(p=3\), we keep three significant digits. Normalise \(x\) to the form \(d_1.d_2d_3 \times 10^{e}\): Since \(x=1.23456\), we look at the first three digits and round if needed. The fourth digit is a 4, which does not round the third digit up. Thus,

\[ fl(x) = 1.23 \times 10^{0}. \]Machine Epsilon: By definition,

\[ \epsilon_{mach} = \frac{1}{2}b^{1-p} = \frac{1}{2}\times 10^{1-3} = \frac{1}{2}\times 10^{-2} = 0.005. \]Relative Error: The actual difference is

\[ |x - fl(x)| = |1.23456 - 1.23| = 0.00456. \]Therefore,

\[ \frac{|x - fl(x)|}{|x|} = \frac{0.00456}{1.23456} \approx 0.00369. \]This is less than \(\epsilon_{mach} = 0.005\), confirming that the error bound provided by machine epsilon accurately describes the worst-case relative rounding error near this scale.